Last Saturday morning Richard and I processed 3 of our roosters all by ourselves. Friday late afternoon I noticed that one of our prize layers, Pearl, was bloodied all over her back and wings. Pearl is one of Richard's favorite hens and when I told of her plight over the phone, he was skeptical about my identifying ability.

"Are you sure it's not one of the roosters? I'll bet it's one of the roosters."

'She's - its grey and white. It's Pearl.'

"Are you sure there weren't any rust colored feathers in with the grey."

'I didn't notice, I was focused on the blood.'

"Go check again."

So I checked again and sure enough, it was Pearl and Richard was upset. He mumbled something derisive about the roosters and said he'd be home as soon as he got off work. In the meantime, I got Pearl out of the coop and into a pet carrier and brought her into our warm utility room to soothe her and make her feel safe. And as I was doing this I was thinking "She doesn't seem that traumatized by the attack". And sure enough when Richard got home, he put Pearl on his lap and examined her in front of the fire.

"This isn't her blood."

'You're sure?'

'She's fine. It's the young roosters. They're getting into fights and wounding one another with their claws and then they hump the hens and bleed all over them."

Richard had been speaking before about these young turks causing trouble in the coop. Red Barber, our proud, colorful, and kind wellsommer rooster who looks as if he walked right off of a corn flakes box, remains our favorite. He rules the roost inside the coop and has a strict code of behavior when it comes to the treatment of all the hens. He brooks no unseemly behavior from the young guys, all of whom are probably his sons. No violent humping, no rape. Of course Red's mating encounters don't exactly look like a chapter out of "The Joy of Sex," but we'll let that slide for the moment. He's heroic and territorial, rushing to the rescue whenever he hears a startled squawk, always on the watch. That's probably the source of the blood, Red putting one of the three in his place.

"That's it!" Richard declared packing Pearl back up, "They're history." And once a Virgo makes a decision, there's no turning back. The 3 roosters were on their way to freezer camp!

The decision made, Richard went into plan mode.

"We'll need the big pot, filled with water."

'The big pot? The soup pot?'

"The canning pot, the big enamel one. What's the sharpest knife we have?"

'Probably the fish filleting one. You're doing it tomorrow?'

"Yes."

'How - what - where are you going to --?'

"I'll string their legs together, hang them by nails on a tree, drain them, and then pluck them."

'But -'

"What's the problem?"

"I don't - I just -" I was suddenly so hesitant and uncertain. I'd always been an advocate for getting rid of more chickens, what was up?

"What's up?"

'What about all the blood?'

"What?"

'There's going to be blood, right?'

"Obviously."

'Shouldn't you get a rubber apron like the processor's up north? Do you really want to get blood on your jacket? It's going to be messy." It was the actuality of doing it, doing it ourselves that was throwing me for a loop. And I knew Richard was actually going to be the one doing it, so why was I upset? Was it because I was still on the fence about eating meat, that every one of these events was leading me to a vegetarian lifestyle? No! I was deciding whether I wanted to take part in it, that I should take part, that this was something new, something big, this was something I knew I should do, that we should experience together, and yet ...

"They wear the aprons because they are surrounded by other workers and there are so many birds that they have to be extra careful about blood getting on them."

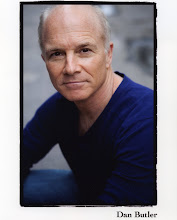

I was going to counter with the fact that the guy up by St Johnsbury where we'd taken 6 of our birds to be processed worked alone and he was in an apron, but Dan, really? And why would we ask this? Move forward. It's happening. Just go with it, decision made. Let it be.

The next day.

Both up early. 6 am. Coffee, fire stoked, birds watered and fed. Richard reminded me that he had to have this done by 11 when he had to leave for another scheduled event, so the clock was ticking.

We were in the coop.

"There they are." One by one Richard pointed out the three that were about to go to a far, far better place. The first was a handsome fellow, big, definitely Red's offspring, though the coloring was different, darker. I could tell Richard was fond of him, I could hear it in his voice, but he was still resigned to the chicken's fate. When describing the next one, however, Richard's tone changed completely. "He's a trouble maker." His voice was flat and fatal, Mr. Death was speaking. The third was pretty scrawny and Richard seemed unsure about including him with the others. But then a resolve took over.

"You're right, let's just do it." I guess I'd been thinking that.

The pot of water was on the stove, close to a boil. It felt as if we were making preparations for a birth. Richard pounded nails into three trees, then came back to the garage to spread newspapers and lay out things for the plucking. We had checked out our knives and none had seemed sharp enough, so Richard called our neighbors who offered several choices of razor sharp instruments.

'How can I help?' I offered.

"I'll catch the birds one at a time, then when I turn them upside down they should calm and that's when I need you to tie their legs together."

'Okay.'

"Then I'll take them back to the trees."

'I don't think I should watch.'

"I don't think you should either." It still seemed so strange and cruel, I was really divided, having seen this creature running around, vital and alive, sure, maybe a trouble maker, but to know we were going to very soon kill it, take it's life. Okay, it's just a chicken, but it seemed enormous to me. I tried my best to get some Barbara Kingsolver mojo going. The best idea I could muster was to be kind to the bird, to tell it thank you, thank you. I stood back by our small coop and watched Richard trudge through the knee high snow to the first nailed tree at the edge of the woods. I could hear him saying thank you to the bird as he did, calming him. The handsome, big bird was first. Richard hung him upside down on the tree then as quick as he could he slit the bird's throat with one swift cut.

"Shit." The knife hadn't been as sharp as he had thought. He cut again. And then again. The bird twitched and flapped. I tensed and must've given a disapproving sound and Richard defended himself.

"That's nerves! You've heard of chickens with their heads cut off running around? That's what's happening." I so wanted to criticize him, tell him he wasn't doing it right, that he was hurting the bird. 'Don't you know what you're doing?! You should know what you're doing!' But I didn't say that. He'd read about it, but I thought this was doing it, doing it for the first time. And there's a world of difference between theory or instructions and the real thing. Oh, but I wanted to denounce him with this authoritative, know it all, voice of great wisdom and reason. But if I knew so much, why didn't I have the knife. Bottom line, I didn't know. I was uncomfortable. It was upsetting. I just stood there mum and witnessed and supported the effort to the best of my ability. Yes, it would've been nice to have cones to put the chickens down into like the processors have, I could see now that that would calm them and keep them from flapping around, but we didn't have them and we were doing our best without them and that was that.

Richard caught the second rooster, the "trouble maker" and again I tied its legs and then followed them both to the woods, standing a little bit closer this time. And this time Richard was more deft and sure of himself.

"It's like they're going to sleep," he assured me having hit an artery cleanly. I could see the raspberry color of its blood syrup the snow. We prepared the third and I walked right up to the tree to watch and Richard explained what he was doing as he did it. And then we waited. 5, 10 minutes went by. They would flap a bit, but slowly life ebbed away. Strange, sad, new.

Next came the plucking. The large enamel pot of boiling water was precariously situated on a tiny hot plate on the garage floor. Richard had read on line that one was to dip the chicken into "just below boiling" water for 45 seconds - I think there was an exact temperature, but we didn't have a thermometer. The immersion would loosen the feathers and make plucking exceedingly easier. The birds had been beheaded by now, most all the blood drained into the snow by the trees. Richard hadn't been looking forward to this step of the game at all and after dipping the bird, he sat down with great consternation on his face, but with the first gentle tug, all this changed. The feathers came out with incredible ease. Amazing! Richard looked up with an open mouth and wonder in his eyes, as if he'd just seen a baby being born. Oh how gorgeous the feathers were, their patterns, the layering, the natural design. What an incredible creation. The smell certainly wasn't pleasant, like a wet winter coat, but the whole process was endlessly fascinating.

And I had to do it myself. I grabbed the next chicken and headed for the hot pot.

"Don't keep it dunked as long this time. It was too hot before and some of the skin started to come off," Richard advised and as he counted out the time he coached me "Okay, now swoosh him around, right, up and down, up and down, good. Now sideways, back and forth. Really get the water all through the feathers ..."

Oh, I almost forgot. After Richard plucked his bird, he dressed it as well. Would that be the term? "Dressed?" Gutted. He'd cleaned plenty of fish in his day, but never a chicken.

'I saw someone do it once and they were able to bring it all out in one tug, almost as if it was in its own sac,' I offered and we walked each other through step-by-step, almost as if we were on a tv cooking show.

'Could we have an overhead shot of this, Frank'

And then after I had the experience of plucking my bird, I too had the experience of gutting and cleaning it. And every step of the way - I don't know how to describe it otherwise - there was such a respect for and honoring of its life. Knowing this bird was going to give us sustenance and nourishment and that our bodies through ingesting it would transform their bodies into energy and calories and life. The whole cycle of life, being part of it in a new way, was so potent and vivid and clear.

We put the newly dressed chickens into a bucket of cold water for a while, then, after cleaning up the garage a bit, we dripped them dry, wrapped them in plastic bags and put them in the freezer.

"This was something major today," Richard said. "Probably the biggest thing we've done together since we moved here."

I think he's right.

Tuesday, February 1, 2011

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment